Today’s post comes a little late, for a good reason. A mentor, colleague, and dear friend, John Hopfield, won the Nobel Prize in Physics today. Hopfield, along with Geoffrey Hinton, won the prize for developing the physics-based mathematics that has enabled neural networks and artificial intelligence. The Princeton Neuroscience Institute has been upended, in a good way.

John was a principal force in recruiting me to Princeton many years ago. He was also instrumental in suggesting a line of research in which two students and I discovered that like silicon-based memory, biological synapses learn in an all-or-none fashion, like binary bits. Neuroscientists, other scientists, and AI researchers around the world owe him similar debts. We are all so proud of him here. (More thoughts here.)

Back to democracy…

Neuroscience also inspires today’s post. I am in Chicago, where the Society for Neuroscience meeting takes place - 22,000 nerds, all here to commune about the brain. Before the conference on my way into town, I realized that Chicagoans have a big role to play in this November’s election. I got a bit worked up about this…

In some ways, national democracy is a distant concept for Chicagoans. Chicago is part of a strongly Democratic state, Illinois. Illinois is home to one of the nation’s worst Congressional gerrymanders, and there are nearly no competitive districts. The Princeton Gerrymandering Project gives it a grade of F. It’s as bad as what Republicans have done in North Carolina.

But that does not mean Chicagoans are without influence.

Two Senate seats, two House seats, and 25 electoral votes

Chicago is one hour’s drive from Wisconsin and Indiana, and two hours away from Michigan. These states more than counterbalance the lack of competition in Illinois.

First, the Presidential race. You do not need a scientist to tell you that this year’s election hinges in large part on the outcome in Wisconsin and Michigan, which are both swing states. Together they account for 25 electoral votes; 270 electoral votes are required to win. On a per-vote basis, Vote Maximizer estimates that in both of these states, individual voters have a power index in the 60’s out of a possible 100. That’s a lot of influence compared with Illinois (power index = 2).

Wisconsin and Michigan also have competitive Senate elections - though honestly, not as competitive as the Presidential elections. This fits with the general observation that Democratic Senate candidates are enjoying polling margins at least 5 points larger than the Harris-vs.-Trump margin.

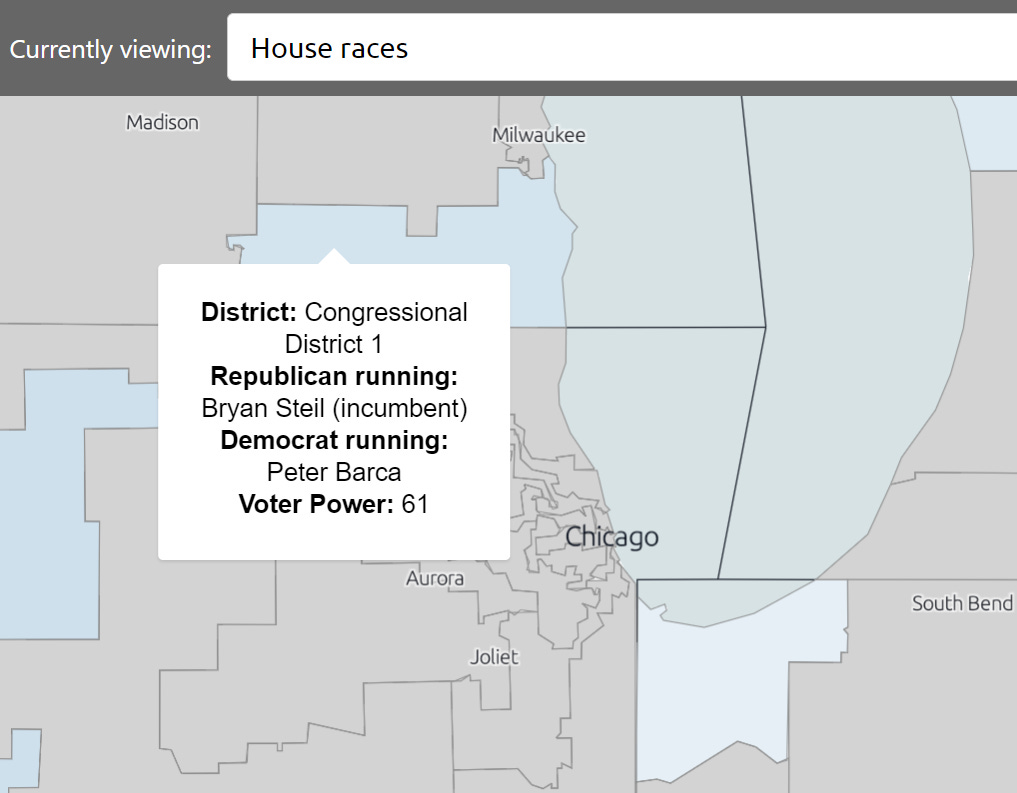

Finally, Wisconsin’s First Congressional District and Indiana’s First Congressional District are both competitive. These seats are held by one Republican and one Democrat. Both could play a role in the tight race for control of Congress. And both districts are quite close to Chicago.

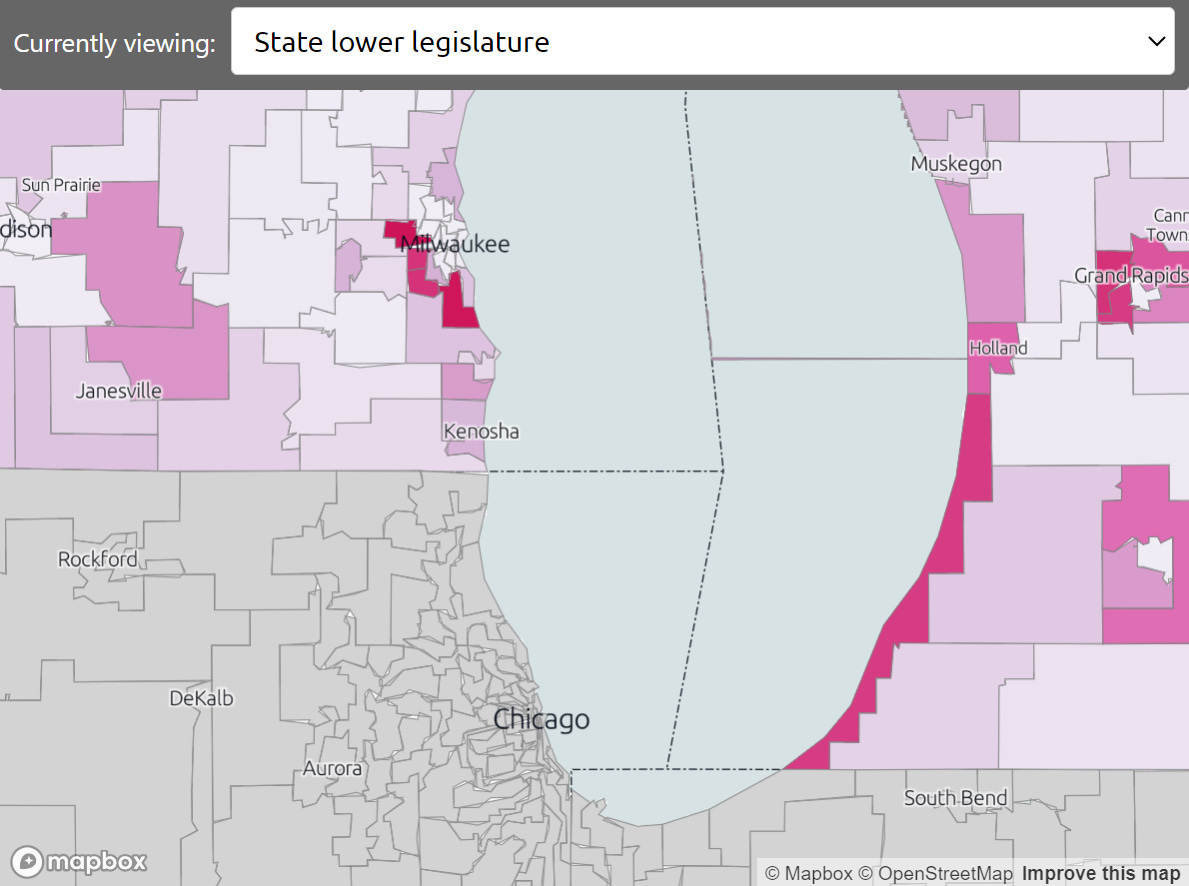

Two legislatures in the balance - thanks to fair districting

Finally, control of two nearby state legislatures is in the balance. This high level of competition in Wisconsin and Michigan arose from active reform efforts. Michigan’s legislative and Congressional maps were drawn by an independent citizen commission (see the Princeton report on this topic here). And Wisconsin’s legislative map was redrawn at the end of a court battle, bringing about a fair map for the first time in a decade and a half (see the deep data dive here).

In both of these states, voters have a reasonable hope at majoritarian rule. That is, whatever party gets more votes will likely end up in control of the Wisconsin Assembly and the Michigan state House. You can look up specific competitive legislative districts here.

Considering the excellent weather here in Chicago this week, it seems like a good time to get out of town - and go make a difference.