In Utah, a light at the end of the redistricting tunnel?

...until 2031, anyway?

Yesterday, a state judge in Utah ordered the implementation of a new Congressional map for the next three elections, from 2026 to 2030. Today in the Deseret News, I unpack the ruling and explain how the judge avoided falling for some misleading definitions of partisan fairness.

Hopefully this ends a years-long saga in which legislators have been looking for a way to re-take some of the power of line-drawing from the citizens who took it from them in 2018 via Proposition 4. If the new ruling stands, Utah voters will likely end up electing 3 Republicans and 1 Democrat to Congress next year.

Here’s the full text of my piece:

Is this the end of the road for redistricting battles in Utah?

by Sam Wang

Yesterday, a state judge in Utah struck down moves by the Legislature that many saw as the latest partisan gerrymander. If the court’s replacement map holds, there is a glimmer of hope that a yearslong, charged political tale may soon end.

This decision was the latest ruling that centers on a law that Utah citizens passed to wrest the redistricting power away from legislators. Passed in 2018, that law, Proposition 4, gave citizens a say in the process and put in place a prohibition on partisan gerrymandering.

This did not stop the Legislature. Instead, they attempted to replace the law entirely. However, the court found that this took away the people’s own legislative power as described in the Utah Constitution.

Judge Dianna Gibson nonetheless gave the Legislature a shot at making amends for its offense. But yesterday, she found that the new map still violates Proposition 4, by unduly shutting out Democrats.

In some states it’s extremely hard to elect even one member of the minority party. Mathematicians have proven that in Massachusetts, Republicans are so evenly spread around the state that there’s no way to draw even one district favoring them. Conversely, in Oklahoma, one-third of voters routinely choose Democratic candidates, but I can’t see any way to draw a district that favors them. In some states, geography is destiny.

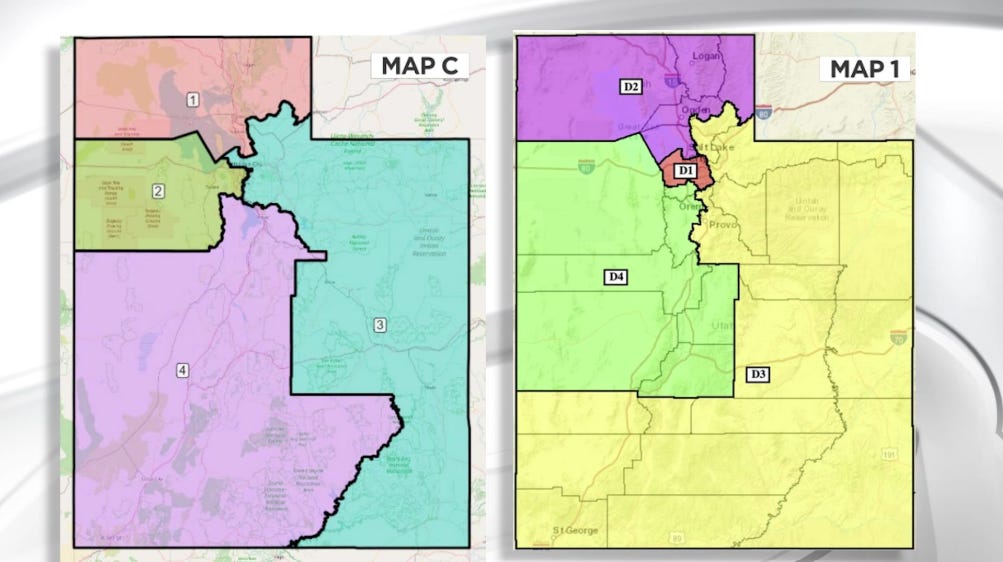

However, Utah is different. Metropolitan Salt Lake City, which contains 1.3 million people, is more than large enough and liberal enough to elect one Democrat. But creative line-drawing by the Legislature cut up this region and gave pieces to every corner of the state, leading to the production of four mini-Utahs, each guaranteed to elect a Republican.

Basically, the Legislature seemed to be executing an old strategy in the gerrymandering playbook: splitting voters with shared interests into groups too puny to elect anyone.

Computer simulations show that a party-neutral process is highly likely to create a district that Democrats can win. In contrast, the Legislature’s plan was a statistical outlier.

By recognizing this fact, the court overrode a recently-enacted Utah law that called for districts to be clustered around the statewide average. In a state like Pennsylvania, where Democrats and Republicans are equally divided, such a rule might treat the parties equally. But forcing Pennsylvania-like standards onto Utah politics is like forcing somebody else’s foot into Cinderella’s slipper. This mathematical jiggery-pokery seemed to some observers a move to thwart the intent of Proposition 4.

What’s next for Utah? In August, Judge Gibson found that under the Utah Constitution, the power to make laws lies jointly between the people and their elected representatives. According to the judge, the people’s expression of that power can be modified, but not overridden entirely. So assuming that ruling holds, Utah will at last have a citizens’ commission in 2031.

Until then, a temporary map is needed. Yesterday, the court accepted a map proposed by citizen plaintiffs that reunites greater Salt Lake City in one district, and creates three surrounding districts that reflect different regions of the state. In 2026, such a map would likely elect a delegation of one Democrat and three Republicans, reflecting the diversity of the Beehive State.

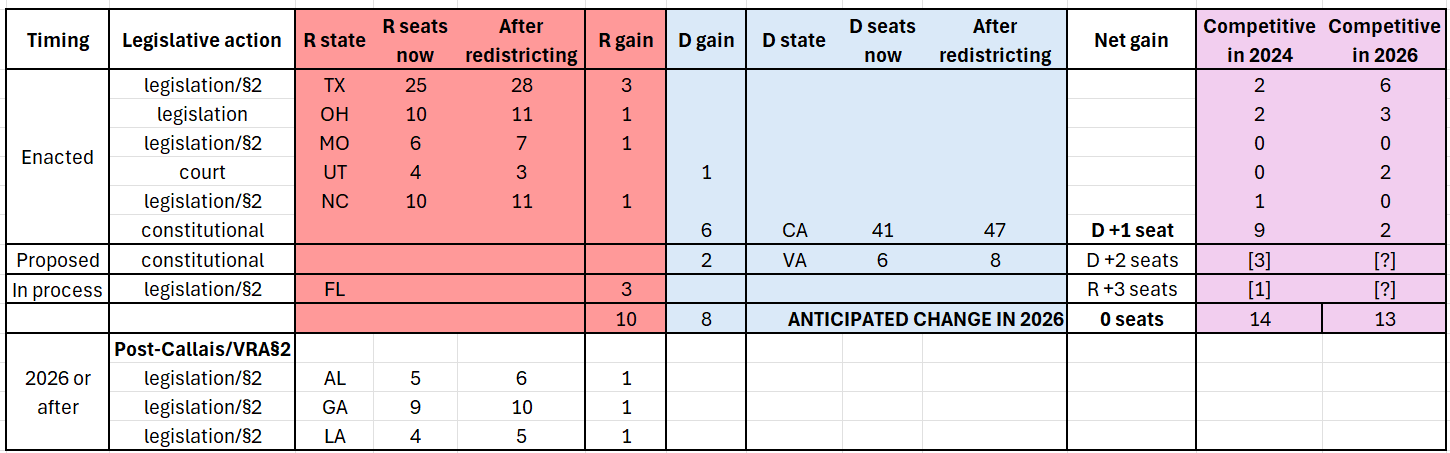

Meanwhile, the national redistricting wars are currently at a stalemate. In the last three months, four states have replaced their congressional maps mid-decade: Texas, California, Missouri and North Carolina.

All told, millions of voters in both parties will be newly deprived of any influence in the next three congressional elections. But as terrible as these wrongs are, at least they balance one another out. As it stands, 2026 elections are still likely to elect a House of Representatives that reflects the will of Americans as a whole.

Thankfully, the festival of gerrymandering may be winding down. A redistricting commission in Ohio reached a bipartisan compromise, and legislators in Kansas and Indiana are dragging their feet about meeting President Donald Trump’s demands to carve up their population like a Thanksgiving turkey.

There is some hope that the next election will elect a Congress that, in many districts, is decided the old-fashioned way: by candidates appealing to voters and voters casting ballots.

A national stalemate

In other news, the approval of Proposition 50 in California will lead to a net gain of about 6 seats for Democrats. Combined with Utah, the advantages gained by Republicans in Texas, Missouri, and Ohio are fully neutralized - but at the cost of reduced competition.

The scorecard above illustrates where we’re at. Jonathan Cervas and I are brewing up some analytics to break down this new stalemate. We’ll write about it soon.

Would love to hear any further discussion of your earlier on Texas: did republicans cut some districts too close for their own good? True in any other red states? Especially given the recent off year results… thanks.

Sam, nice analysis. In downgrading Ohio competitive districts from three to two, was it the Toledo district that you discounted? The Ohio Dem leaders are claiming they think that one (and the Cincinnati district) are still winnable in 2026. And OH CD13 will still be strongly contested.