Reprogramming the simulation

Primary elections as a pivot point for moderate candidates

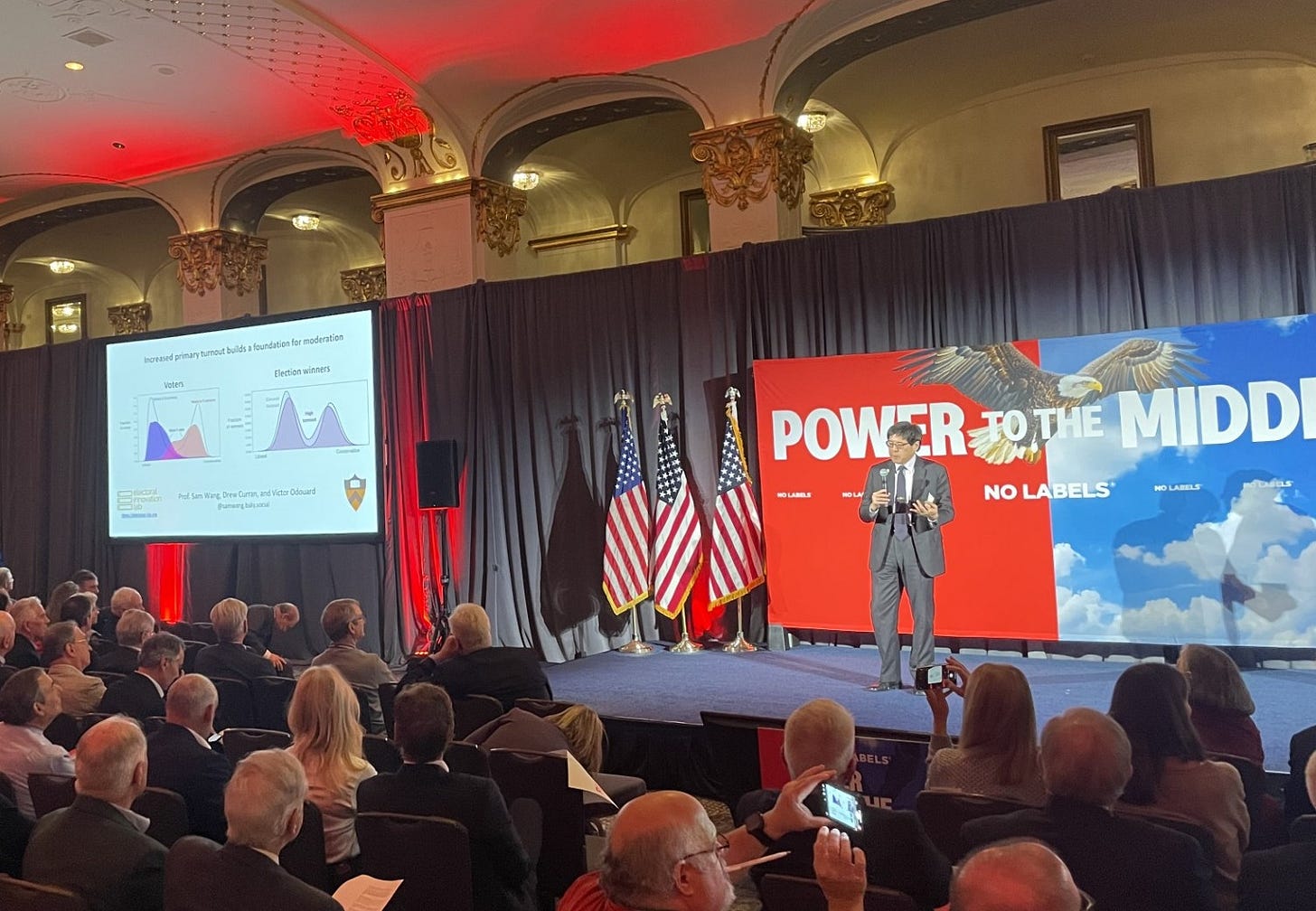

At last week’s No Labels conference, that centrist organization’s future priorities came under lively discussion. Despite widespread concerns about disruptive (and possibly destructive) change in 2025, and despite the crash of their biggest effort, a “unity” Presidential ticket, they want to get back into the mix. But what will they do?

An interesting possibility arose: they might get into democracy reform. If they were to expand beyond playing under the existing rules of the game and toward changing the rules, that could help them achieve one of their major goals - and be cheaper than political campaigns.

The limits of playing by today’s electoral rules

In 2024, No Labels made national headlines for their attempt to run a Presidential “unity ticket,” meant as an alternative to the Biden (and then Harris) and Trump candidacies. As I wrote before, under current electoral rules, such a ticket hurts whichever party is closer to them ideologically. In such a backfire effect, you hurt the one you love (or at least dislike less). The problem of a spoiler candidacy is a major challenge to any organization that wants to build moderation in today’s electoral system.

Much of last week’s discussion focused on “playing the ball where it lies,” i.e. dealing with the new House and Senate. To the extent that the new administration’s disruptive priorities came up, it was in the context of the close division of these chambers, and ways to act through existing legislative and lobbying processes.

But another possibility is to change the rules of the game.

Getting primaried

At the No Labels meeting, many elected officials expressed the fear that acting in the general interest and against their party’s position might lead to being challenged and defeated in their party’s primary. This concern is so common among politicians that it has become a verb: being primaried.

In nearly all states, partisan primary elections determine who goes on to the general election. Turnout in primary elections is typically 20% of a party’s membership. However, in recent Gallup surveys, Democrats and Republicans combined add up to only 58% of Americans. Therefore for nearly all partisan offices, only 12% of Americans - less than 1 in 8 - end up determining what choices are available in the November general election. And thanks mostly to geographic sorting (and some gerrymandering), the general election is no contest at all. All of this calls to mind the words of Boss Tweed: "I don't care who does the electing, as long as I get to do the nominating."

This matters because primary voters are not representative of all voters. They are more coherent in their ideological views than the vast majority of Americans. And since Democratic and Republican voters have become highly separated in their views on many issues, that means that if a candidate wants to reflect the views of primary voters, that candidate also has to be ideologically pure. In other words, the current election system provides a strong incentive for politicians to take public positions that are far from the median voter.

Extreme voters elect extreme representatives

Here at Princeton, Drew Curran, Victor Odouard, and I have been modeling how this ideological purity gets translated into representation. We have also done computer simulations to show how ideological purity is enough to account for the extreme election winners we see today. This has given us a way to explore the effectiveness of various reforms to mitigate that extremism.

What we've done is investigate different ways in which the fear of primaries might possibly be reduced. To understand what's going on here, let's look at some key statistics.

Looking at the distribution of primary voters from left to right, we can see that based on our analysis of their issue stances, they are quite extreme. We analyzed data from the Cooperative Election Survey to identify the principal axis of variation in political attitudes – effectively reducing the high-dimensional space of political opinions to a single left-right dimension.[1] Then we placed others on that axis.

This suggested to us the possibility that increasing primary turnout could lead to more moderate voters and more moderate nominees. We tested this hypothesis by simulating many thousands of elections.

We modeled the typical U.S. election system: Democratic and Republican party primaries that each produce one nominee, followed by a face-off between the two in a general election. We created primary candidates from various points on the left-right axis, and had voters pick whatever candidate was closest to them, both in the primary and the general.

In these simulations, increasing primary turnout indeed led to more moderate winners:

Even more intriguingly, we found that replacing traditional party primaries with a single all-party primary – where all candidates, regardless of party affiliation, compete in a single contest – was even more effective at producing moderate outcomes.

To contrast these findings, we also simulated a scenario with compulsory voting in the general election while maintaining the current primary system. This intervention was completely ineffective at moderating outcomes:

The reason is clear. By the time the general election comes around, it's too late – the horse is out of the barn, and it's no longer possible to moderate the candidates because the nominations have already been set. This is Boss Tweed's dictum in action.

The Concept of the Pivotal Voter

The fundamental principle here is simple: every electoral system has pivotal voters, the ones who are decisive in determining who wins. To get more moderate outcomes, those pivotal voters need to be as close to the median voter as possible.

In a strongly partisan district, which can happen naturally or through gerrymandering, the pivotal voter is one who votes in the primary election. In which case:

Increasing primary turnout will bring in voters who are closer to the center; and

Letting non-affiliated voters participate recruits even more such voters.

Note that this is pretty close to No Labels slogan, “Power To The Middle.” They’ve been trying to achieve their goal through campaigning and lobbying. Their next move might be to expand into democracy reform.

Can Reform Move the Pivot Point?

These pivot points can potentially be altered indirectly, either by federal or state law.

At a federal level, No Labels is considering the idea of a National Primary Day. Their theory is that if primary day is a national event, it will be more salient to voters, and more of them will turn out.

Another change is possible at the state level: combining primaries into a single, all-party primary. California, Washington, and Alaska already do this (and in state legislative primaries only, Nebraska and Louisiana do it too). And when it comes to being primaried, members of Congress from these states have considerably less to fear from their own party than in other states. One prominent example is Senator Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, who said at the No Labels conference that she wasn’t attached to the Republican party label.

Switching to an all-party primary is not a crazy reform. Such a measure almost passed in Montana this year, getting 49% of the vote. It’s easy to imagine ballot initiatives on this subject doing better in 2026.

The big idea

These aren’t the only reforms that could work. Any change that moves the pivotal voter closer to the ideological center would have similar effects.

So far we’ve explored two possibilities increasing turnout in primary elections, and implementing an all-party primary system. Either of these reforms, or even both, offer one path toward reducing political polarization in our elected officials.

Note:

[1] On the CES, we analyzed answers to over 60 questions on various issues using a technique called binary principal component analysis. This allowed us to find the contribution of each question to different dimensions. Much of the variation in answers could be explained by one axis, the “first principal component.” We could then place voters along that axis. For each voter we had a variety of CES data: whether people were registered to vote, whether they voted in the 2020 and 2024 general elections, whether they voted in the 2022 primary, and their partisan affiliation. All of this allowed us to characterize voters, nonvoters, and others.

Correction - Maine has a ranked-choice general election, but not an all-party primary. Thanks to Ben Sheehan for catching that. Also, a few states have all-party primaries for state legislature only, Nebraska and Louisiana.

For a list of how each states' primaries are conducted, see this Ballotpedia article: https://ballotpedia.org/Primary_election_types_by_state

I believe this is consistent with the views of "www.ReformElectionsNow.org/about/" as well as the Academics Task Force on Election Reform, whose book was published this month: https://www.rienner.com/title/Electoral_Reform_in_the_United_States_Proposals_for_Combating_Polarization_and_Extremism - Have you met yet with one of the editors of that book Ned Foley, who is a Princeton Fellow this year on leave from Ohio State's Election Law Institute? I am sure you are also familiar with the work by Open Primaries on Nonpartisan Primaries, among other related options. Please contact me if you have a chance: otten@alumni.princeton.edu