So...what happens *after* 2023's most important election?

In which I game out what will be needed to overturn the nation's most extreme gerrymander

If the secret to great comedy is timing, then my comic career is doomed to fail. Six weeks ago I wrote that Wisconsin’s state Supreme Court election was the most important race of 2023. Now in this weekend’s New York Times, Michelle Goldberg has gotten around to saying the same thing. Her front-page placement in Opinion brings important background and perspective, and brings excellent exposure to this important subject.

Today I offer a look ahead about what happens next, assuming that Judge Janet Protasiewicz wins tomorrow. The resulting court is nearly certain to take a hard look at Wisconsin’s legislative maps, which form the most extreme gerrymander in the country. To overturn the map, the Wisconsin Supreme Court needs a legal theory - and it needs one that can avoid hostile action by the U.S. Supreme Court.

The most extreme gerrymander in America

Gerrymanders can target individuals, racial groups, and whole political parties. And when a state is close to 50-50 in its voter composition, a partisan gerrymander can freeze out the opposition from ever taking power.

There are many ways to measure partisan advantage. One of the oldest metrics is partisan bias, which quantifies how hard it is for a party to get 50-50 control of a chamber. Here, based on Princeton Gerrymandering Project metrics, are a few partisan bias scores:

Indeed, Wisconsin has the highest partisan bias scores in the nation. This isn’t because of political geography: other states such as Pennsylvania have similar rural/urban divides, but represent both parties equitably. But in Wisconsin, Republicans are guaranteed to stay in power no matter what happens - and are close to a legislative supermajority with not much more than 50% of the statewide vote. Truly, the state lacks representative democracy.

The two runoff candidates, Janet Protasiewicz and Daniel Kelly, represent opposite sides of this issue. As I wrote in February, Kelly defended the previous, very similar gerrymander in court in 2012. Protasiewicz has taken the opposite stance, and is willing to intervene with the current map. The two candidates likewise differ on many aspects of voting rights, which may impact the conduct of other elections, including the 2024 presidential race.

Anti-gerrymandering provisions in Wisconsin state law

If Protasiewicz wins, as is currently expected, the Court has to define partisan gerrymandering under state law. The U.S. Supreme Court took the federal path off the table in their Rucho v. Common Cause decision. But the Wisconsin court has numerous provisions at its disposal.

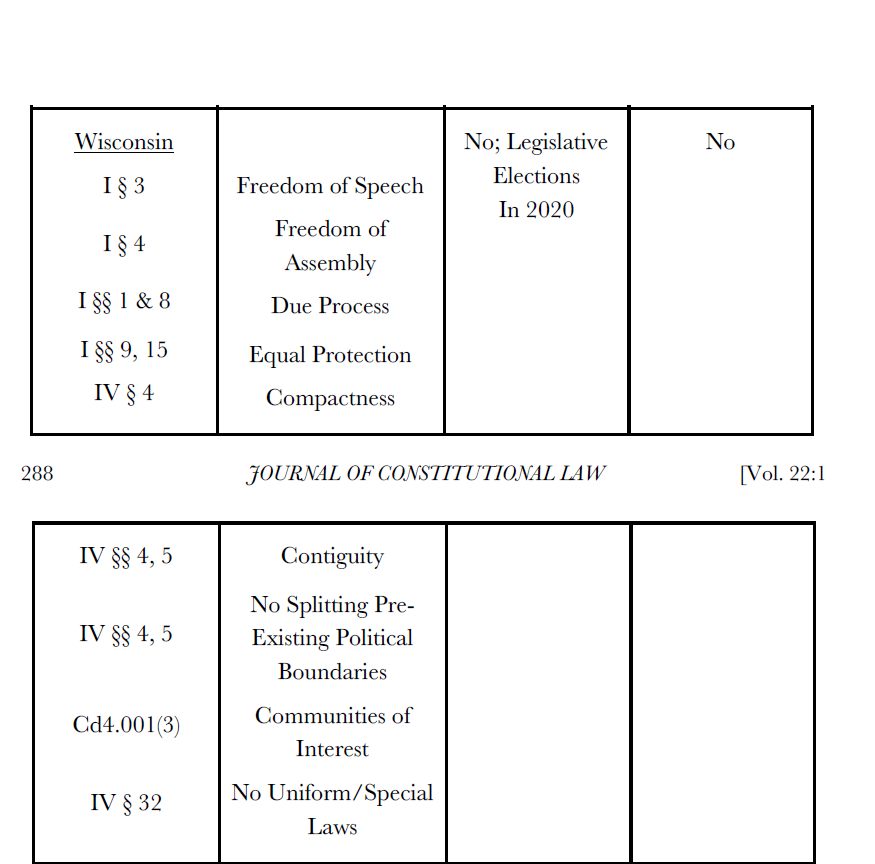

In a law article, Ben Williams, Rick Ober, and I reviewed these provisions - as well as those in all fifty states. Wisconsin law includes a host of applicable protections, including freedom of association, a requirement for compactness and contiguity of shape, no splitting of pre-existing political boundaries, preservation of communities of interest, and equal protection of voters:

Some protections echo provisions found in the U.S. Constitution's First and Fourteenth Amendments. Therefore, for intellectual guidance, the court could emulate the arguments laid out in Justice Elena Kagan's dissent in Rucho. They just have to the swap out the federal sources quoted by Justice Kagan, and swap in the corresponding Wisconsin law and constitution.

In fact, it is a shame that the U.S> Supreme Court backed away from establishing a national doctrine. A preceding case, Gill v. Whitford, laid out the principles even more clearly. Both Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Kagan spelled out some fairly clear reasoning:

In addition to all of this, there is state-specific law. The Wisconsin Supreme Court can cite court cases in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and North Carolina, where state courts have constructed arguments based in their respective laws and constitutions.

Finally, the Wisconsin Supreme Court can even quote itself. Justice Brian Hagedorn, the swing vote in the 2022 redistricting disputes, relied on the communities-of-interest provision in his rulings.

Landmines with the U.S. Supreme Court

Despite the difficulties in redistricting last year, the 2022 Wisconsin Supreme Court does deserve some credit. Although they were conservative in outlook, they still almost succeeded in undoing the legislative gerrymander. They were held back by one thing they weren’t willing to do: draw their own maps.

The court relied on the litigants - Governor Evers on one side, and the legislature on the other - to propose specific maps, at which point the court chose between them. This ended up being a problem, since the U.S. Supreme Court called into question specific reasoning by Governor Evers. The Supremes said that Governor Evers interpreted the Voting Rights Act incorrectly by citing a need to draw a new Assembly district to represent Black citizens. So the case went back. Time ran out, and the Wisconsin court had to chose the legislature’s alternative. The Princeton group gives that map an "F":

Doing things differently in 2023

It’s clear that the Wisconsin Supreme Court can't rely on the US Supreme Court to have their backs. Quite the opposite.

Here are some ideas for how to address partisan gerrymandering at the state level, and reduce the likelihood of federal interference.

Do not cite the Voting Rights Act. Protection of race-based voting rights under the VRA is being steadily eroded by the Supreme Court. And the last remaining part, Section 2, may be weakened further this year.

Use state-only provisions. Build an argument that does not rely on provisions appearing in the U.S. constitution. Wisconsin law says to not split political boundaries and to maintain communities of interest. It is possible to evaluate community splits rigorously using public databases such as Representable.org and Districtr, and using mathematical definitions that my research group has developed. After that, equal-protection and freedom-of-association arguments can play a role - but to do so, quote state law.

Draw maps. Certainly the court can ask litigants to provide map alternatives - but the court needs to prepare for the possibility of drawing its own maps. The conservative view is to avoid court-drawn maps, which could be viewed as “legislating from the bench.” But in voting rights cases, imposing a remedy is well within standard existing judicial practice.

This last step is important. Courts in Virginia, Connecticut, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and other states have drawn maps and ended up with relatively equitable results. Failure to take that step has led to suboptimal outcomes, for example in Ohio, where Republicans retained a substantial advantage in a Congressional map, and in Maryland, where Democrats did the same.

One final note: some of you may be concerned about the Independent State Legislature doctrine. I wouldn’t worry about that too much. First, as I wrote in the Washington Post, the doctrine is likely to backfire on Republican proponents. Second, and more importantly - the doctrine applies to federal, not state elections. So it’s not relevant to the important question of whether the citizens of a state get to govern themselves.

Now…Wisconsinites (or cheeseheads, if you like) - go out and vote tomorrow like your democracy depends on it!

Well, we got a good return on investment for your advice earlier this year that the Wisconsin Supreme Court election was this year's most important race. I hope the few dollars I sent to the Dem candidate helped put her over the top.

But now we have the cliff hanger in the State Senate race, which could give the R's a super-majority. With it, says the R candidate, if he wins he would consider an attempt to impeach the new Supreme Court justice before she has heard a single case!